The Changing Terms of Health Aid: America First and Africa’s Bilateral Turn

Chioma Nnamani and Yasir Jamal Bakare

Global health aid extends beyond improving health outcomes. It shapes who sets priorities, controls resources, and decides when support ends. Across Africa, these dynamics are becoming more visible as countries enter new bilateral health agreements with the United States under the America First Global Health Strategy. The approach aims to reduce dependency by prioritising measurable outcomes and stronger national systems, while narrowing the scope of its obligations. This signals a shift away from open-ended, multilateral aid models to shared financial responsibility.

Several African countries have signed bilateral Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with the United States under the America First Global Health Strategy. These agreements designed as government-to-government compacts include joint commitments on financing, U.S. funding reductions, and performance expectations over multiyear periods.

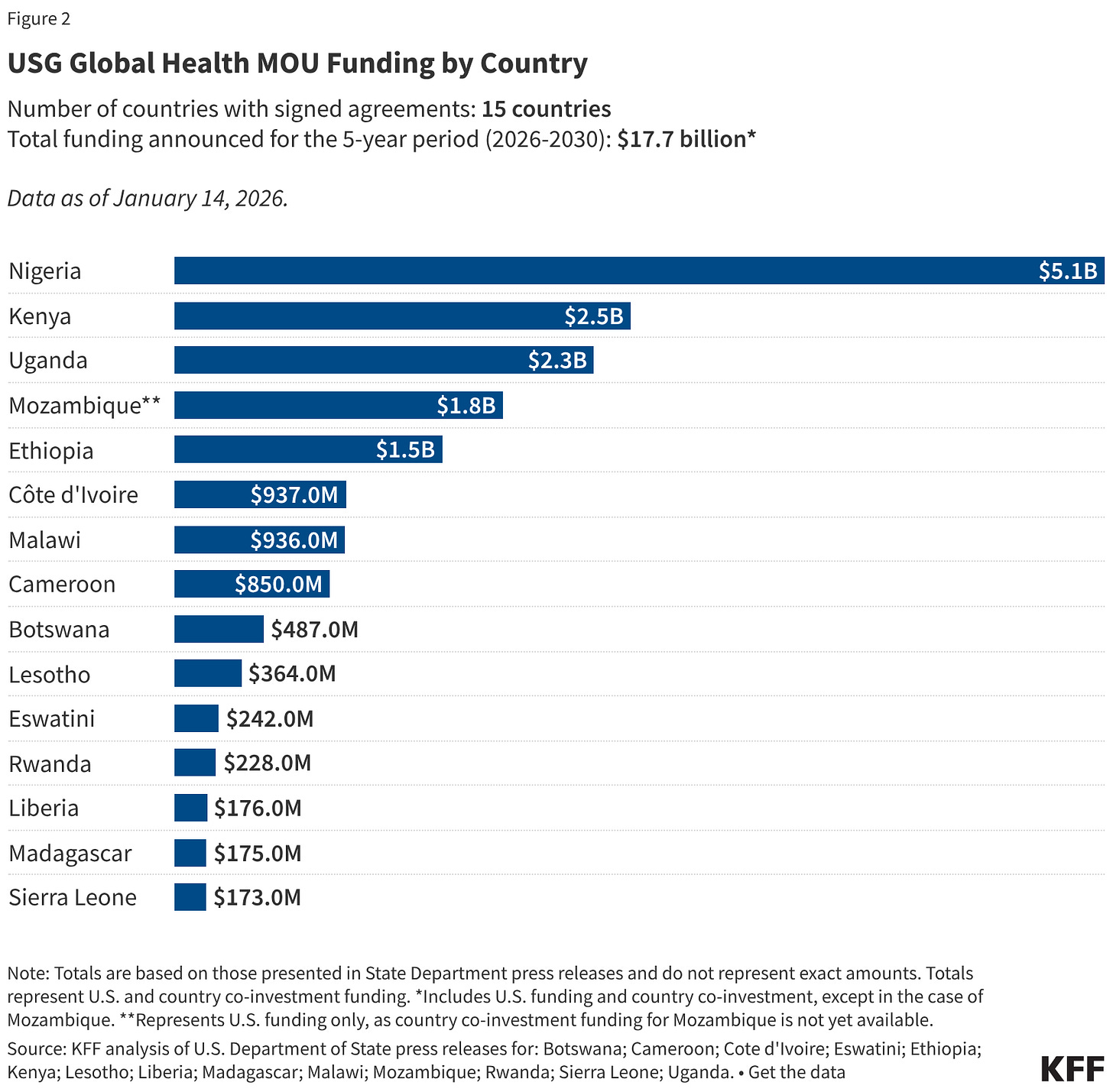

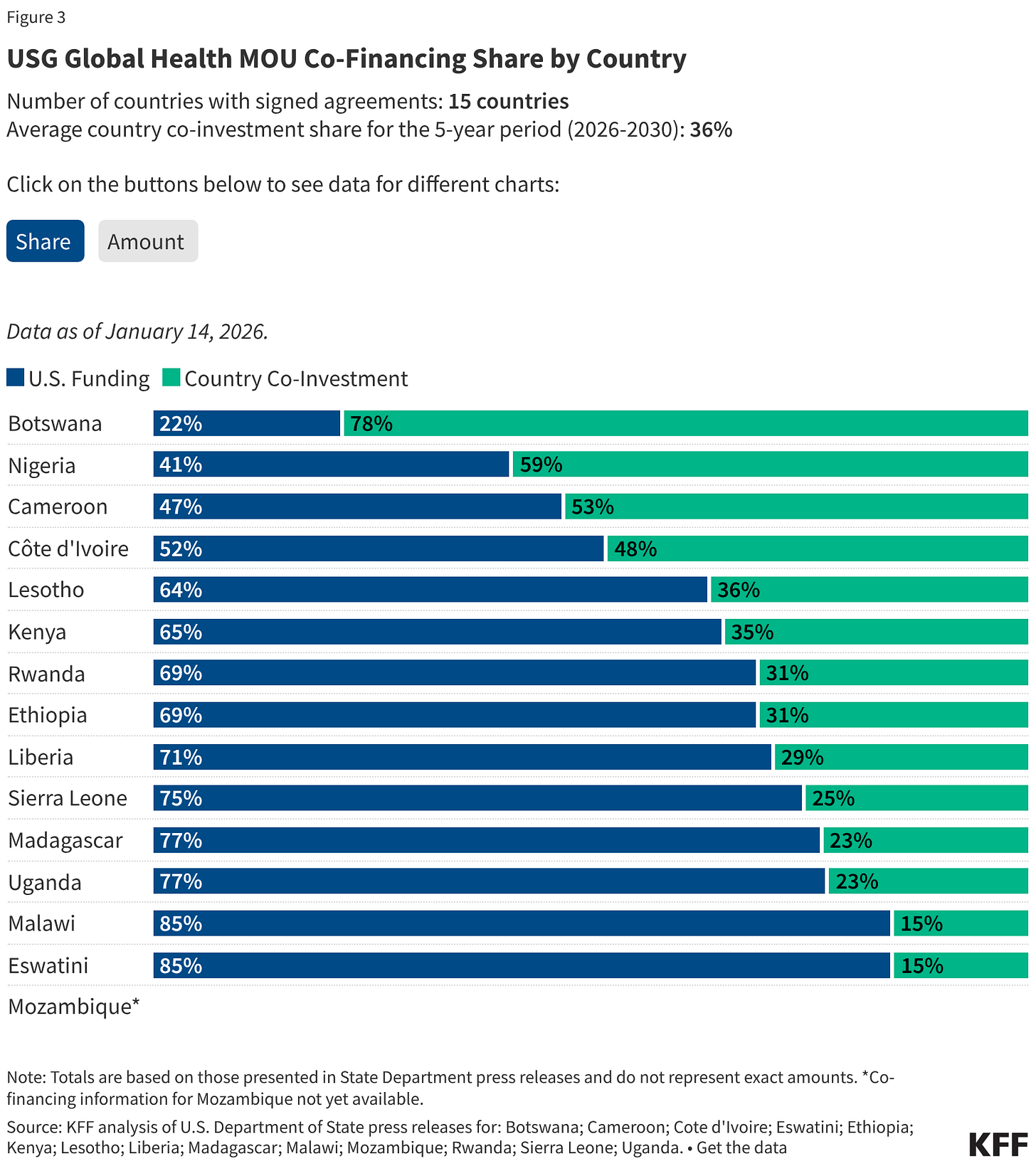

In East Africa, Kenya became the first, securing a five-year agreement valued at $2.5 billion, of which $1.6 billion is expected from the United States and $850 million from the Government of Kenya. Rwanda followed with a five-year MoU that includes up to $158 million in U.S. support and a $70 million commitment in increased domestic health spending. Uganda has also signed a five-year agreement valued at nearly $2.3 billion, combining up to $1.7 billion in U.S. support with a $500 million domestic co-investment pledge. Ethiopia joined with an agreement valued at $1.466 billion, including a $450 million domestic co-investment commitment.

In West and Central Africa, Cameroon made commitments of up to $400 million in U.S. support, alongside a $450 million increase in domestic health spending. Côte d’Ivoire entered a larger arrangement, combining up to $487 million in U.S. support with $450 million in new domestic health investment, of which $125 million is earmarked for frontline health workers and essential commodities. Liberia’s agreement is valued at $176 million, with $125 million expected from the United States and $51 million in domestic co-investment. Nigeria, the largest signatory to date is committing nearly $3.0 billion in new domestic health spending with close to $2.1 billion in planned U.S. support, while Sierra Leone’s agreement is valued at over $173 million, with $129 million from the United States and more than $44 million in domestic co-investment.

In Southern Africa, Botswana has signed a three-year health cooperation agreement of $487 million, with $106 million expected from the United States and a $381 million increase in domestic health spending. The agreement comes with a five-year data-sharing arrangement aimed at modernising health information systems and strengthening disease surveillance and outbreak preparedness. Mozambique has signed a five-year agreement, under which the United States plans to provide up to $1.8 billion to expand HIV/AIDS prevention, including the rollout of lenacapavir, advance malaria prevention, and strengthen maternal, newborn, and child health. Malawi also signed an MoU valued at $936 million and under the agreement, the U.S. intends to provide up to $792 million over five years, while Malawi commits an additional $143.8 million in domestic health spending.

Madagascar’s agreement is valued at over $175 million, while Lesotho and Eswatini have entered agreements worth $364 million and $242 million respectively.

These commitments, however, carry no guarantees. MoUs are not legally binding, and release of funds depends on both congressional approval and national budget allocations in each country.

The First Tests of a New Aid Model

The real measure lies in how quickly and clearly these agreements move from paper to practice. Implementation, disbursement, and domestic accountability mechanisms will determine whether they translate into real health gains or remain largely diplomatic instruments.

In East Africa, Kenya has moved furthest into the operational phase of the new bilateral model, making it the first country where the implications of implementation have surfaced publicly. Legal challenges and civil society pushbacks have led a Kenyan court to temporarily halt aspects of the agreement, citing concerns that data sharing provisions could undermine constitutional privacy safeguards and national data protection laws. The case has made Kenya the first testing ground for how these new agreements interact with domestic legal systems, public accountability, and data governance frameworks.

Nigeria presents a different set of challenges. Despite being the largest signatory under the America First framework, the full text of its bilateral health MoU has not been made public, raising questions around transparency, legislative review, and public oversight.

Civil society organisations and health accountability advocates have called for greater disclosure and parliamentary engagement, particularly given the agreement’s conditionalities and its implications for national health priorities. Concerns have also been raised about continuity, as the framework allows U.S. authorities to pause or terminate programmes that no longer align with U.S. national interests. For domestic stakeholders, this reinforces the need for stronger safeguards to ensure predictability and alignment with long-term national plans, highlighting a widening gap between diplomatic momentum and execution.

Why This Matters

The America First Global Health Strategy represents a deliberate shift from traditional, open-ended aid toward time-limited, bilateral, co-financed agreements that demand new absorptive capacity from partner governments, not just signatures. Despite broad political support, this fragmented approach could weaken long-standing multilateral coordination mechanisms and create implementation challenges at the national level. These dynamics are already visible in the legal scrutiny and public debate around data governance in Kenya, where courts and legislators are shaping how the agreement will unfold.

Meanwhile, countries are negotiating a global Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing (PABS) system under the World Health Organization’s Pandemic Agreement, with talks set to resume in Geneva from January 20–22, 2026, and bilateral MoUs that include pathogen or health data-sharing could overlap with these multilateral negotiations, creating friction between U.S. agreements and long-term global frameworks for equitable pathogen sharing and pandemic preparedness.

The bigger question remains whether these parallel tracks will complement each other or create new tensions at a moment when alignment, accountability, and negotiating power matter most.