In August 2024, mpox was declared a continental and global health emergency as a severe strain spread across Africa. One year later, Africa CDC and WHO reflect on progress made, and the urgent gaps that remain.

In August 2024, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) declared mpox a Public Health Emergency of Continental Security (PHECS), while the World Health Organization (WHO) designated it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). These declarations highlighting the scale of the crisis following the rapid spread of the more aggressive Clade 1b strain across Africa, raising the stakes for global health security and underscoring the urgent need for coordinated action at both regional and global levels.

First identified in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), this novel variant carried mutations suggesting increased human-to-human transmissibility. By 15 September 2024, the outbreak had escalated to over 29,000 suspected cases across the continent.

Due to the rapid spread of the virus in the DRC and rising fatalities, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention elevated the crisis to a Public Health Emergency of Continental Security (PHECS) which is its highest level of alert. The presence of the virus in neighbouring countries like Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda reflected a clear continental threat with global implications.

One Year On: Tracking Africa’s Mpox Response

On 14 August 2025, exactly one year after mpox was declared a global public health emergency, WHO and the Africa CDC held a joint media briefing to reflect on the journey so far and the continent’s response.

Speaking at the briefing, Dr. Otim Patrick Ramadan, Programme Area Manager at the WHO Regional Office for Africa, highlighted that mpox “remains a serious public health challenge in Africa,” even as progress have been made in containment efforts. He noted that since the August 2024 declaration, 28 countries have reported more than 174,000 suspected cases and nearly 50,000 confirmed cases, alongside 243 deaths.

Ramadan added that while 22 countries are still facing active outbreaks, there are signs of progress as Côte d’Ivoire has brought its outbreak under control, surpassing 42 days without new cases, while Angola, Gabon, Mauritius, and Zimbabwe have each gone more than 90 days without a single confirmed case.

In the past year, WHO and Africa CDC have coordinated efforts under the Global Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan and the Continental Mpox Preparedness and Response Plan, now in its second phase. Working with partners, they established a joint incident management support team, rolled out vaccine access mechanisms, provided essential logistics support, and worked closely with countries to strengthen their response systems.

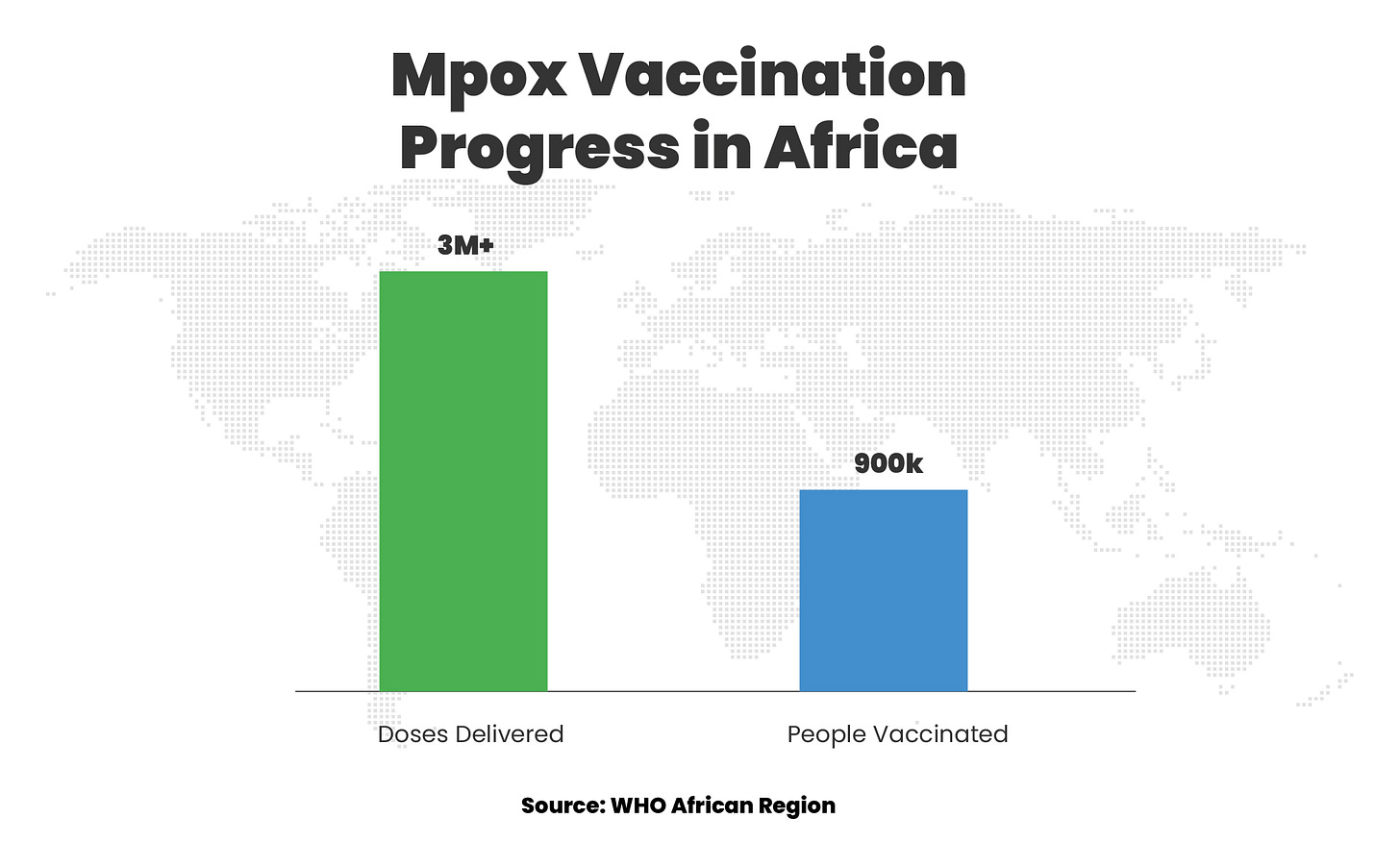

According to Ramadan, over 3 million doses of mpox vaccines have been delivered across the region, with around 900,000 people receiving at least one dose of the mpox vaccine. “Thirteen of the 22 affected countries currently have vaccine deployment plans, and eight are actively vaccinating high-risk groups,” he said. “Other achievements include the deployment of 112 international experts, training of 4,000 health workers, and $4.5 million worth of protective and laboratory supplies to 30 countries. In total, about $76 million in donor funding has been mobilised to strengthen response operations in affected countries. Testing capacity has also improved in the Democratic Republic of Congo, rising from 20% to 65%.”

Dr Nicksy Gumede-Moeletsi, WHO Regional Advisor for Laboratory and Genomic Surveillance, added that this increase in testing capacity was made possible by the expansion of laboratories in the country, from two to the current number of 27.

Addressing Gaps to Sustain Progress

“Stigma still deters people from seeking care and testing, fuelling transmission,” said Aminata Grace Kobie, WHO Technical Officer for Health Promotion. She noted that “WHO and partners have responded with infodemic management strategies, including culturally sensitive messaging, survivor testimonies, and partnerships with the media to promote responsible reporting.”

Another concern raised during the briefing was limited vaccine access. In response to questions, WHO explained that in collaboration with GAVI, UNICEF, CEPI, and Africa CDC, it established a global solidarity mechanism in September 2024 to improve equitable access to vaccines.

However, vaccine supplies are still reliant on donations and remain insufficient for mass vaccination. “The doses we have are being used to control outbreaks and curb transmission by targeting high-risk groups identified by the epidemiological investigation,” Ramadan explained, adding “For now, the goal is to interrupt transmission and when the vaccine doses are more and our aim has been achieved, we can focus on building immunity”.

He stressed that urgent action is still required to secure additional vaccines, scale up operational funding, and strengthen cross-border coordination to reduce the risk of spread in new areas and beyond the continent.

Outlining the next six months, Ramadan noted that priorities include expanding community-based surveillance in high-risk areas, procuring and distributing essential supplies to remaining hotspots, supporting the integration of mpox response into other health programmes for sustainability, and maintaining targeted vaccination while advocating for more funding for vaccine deployment.

“It is critical that we sustain what works, and what works includes rapid case detection, timely targeted vaccination, strong laboratory systems for early confirmation, and active community engagement.”

~Dr. Otim Patrick Ramadan, Programme Area Manager at the WHO Regional Office for Africa

This shows that while progress has been made, keeping up with the effort would be important in fully containing mpox in Africa.

Why this matters

Public health threats do not respect borders. Mpox, like COVID-19 before it, reminds us that outbreaks are just one plane flight away. For African countries, this means vigilance must never fade once the headlines quiet down. The systems and capacities built during an emergency response, from surveillance to laboratory networks and rapid communication channels, are not temporary tools, but essential infrastructure for resilience. Sustaining these investments, even when cases decline, is what separates countries that are constantly on the back foot from those that can detect, respond, and contain threats before they spiral. Mpox may not be as threatening as it was last year, but the lessons it offers are urgent and enduring for Africa’s health security.