From Financing to People-Centred Care - Building Primary Health Care That Works for Africa

Ibukun Oguntola

At the 4th International Conference on Public Health in Africa (CPHIA 2025), experts agreed that achieving Universal Health Coverage in Africa must start where health begins — in communities, through primary health care.

Dr. Amit Thakker, Executive Chairman at Africa Health Business, opened with a clear call:

“Health care doesn’t begin at the hospital; it begins at home.”

He noted that roughly 70% of outpatient ailments could be avoided, pointing to prevention and early detection as the most cost-effective tools for better population health. Dr. Thakker pushed beyond the usual calls for more money to argue for smarter, more context-sensitive financing: strategic allocation that prioritises prevention, removes geographic barriers, and extends services, equipment and trained personnel beyond urban centres.

With Official Development Assistance declining, Dr. Thakker urged countries to innovate domestically. He proposed bespoke, country-level health bonds, citizen-driven instruments designed to generate resilient, transparent financing for primary care, and appealed for private sector commitments, notably the idea that even 1% of corporate profits channelled to health could be transformative. He also advocated for crowdsourced platforms to democratise contributions to community health and for socially responsible corporations to embed health equity into their core missions.

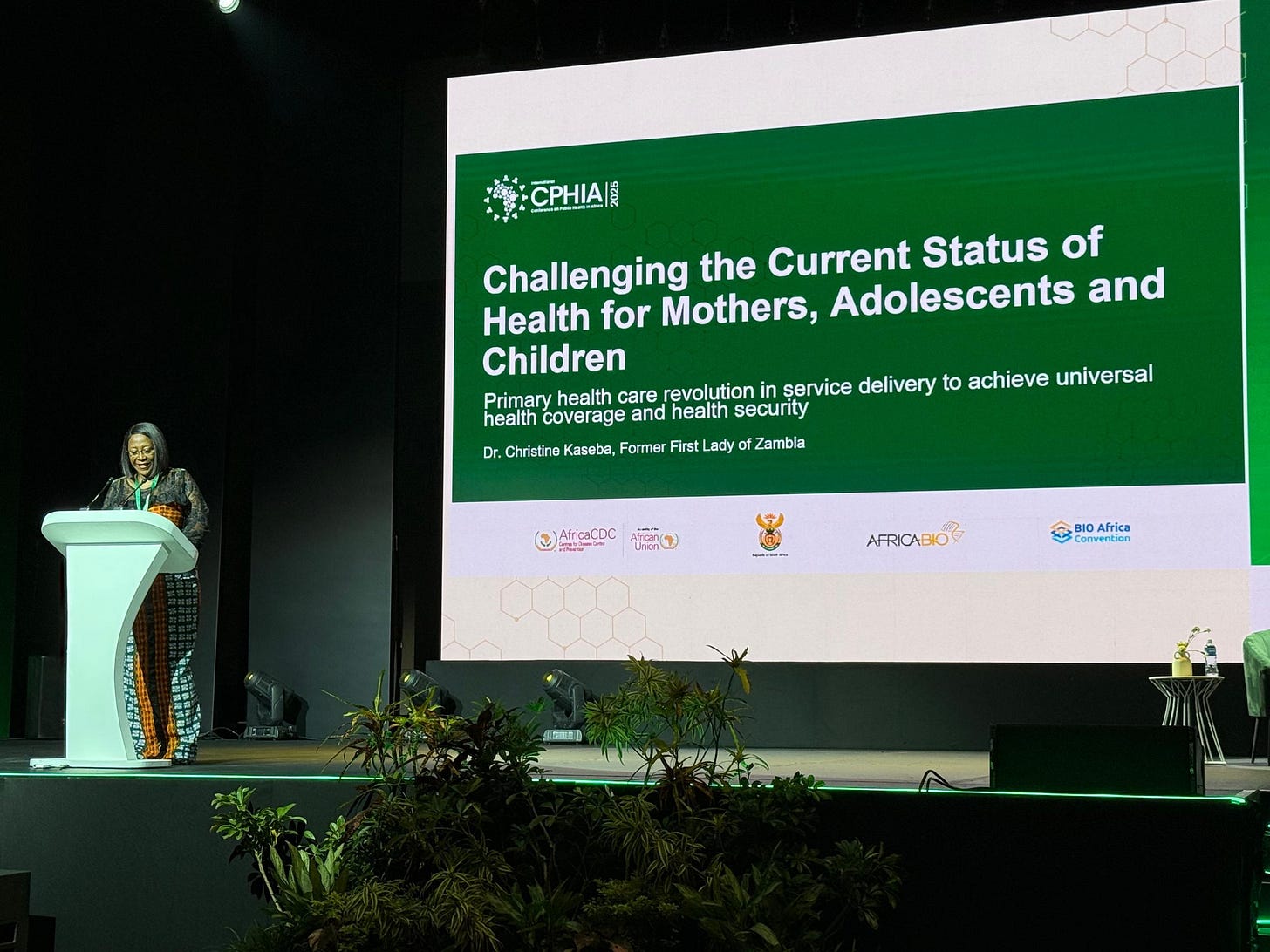

Dr. Christine Kaseba, Former First Lady of Zambia, shifted the conversation to people-centred care for women, adolescents and children. Challenging narrow definitions of “women’s health,” she emphasised that care must span adolescence, pregnancy, motherhood, menopause and the years beyond. Even with maternal mortality rates declining from 727 to 441 deaths per 100,000 live births, Africa still accounts for about 70% of global maternal deaths. In 2023, 77% of adolescent girls with HIV globally were in Africa, highlighting persistent vulnerabilities.

Dr. Kaseba argued that the drivers of poor health outcomes are systemic: weak and costly PHC, fragmented vertical programmes, workforce shortages and burnout, low community engagement, and systems that fail to respect cultural contexts. Her prescription is practical: shift to community-centred, human-centred PHC; invest in community health workers and mid-level providers; integrate maternal, newborn, child and adolescent services; scale digital tools for better data and decision-making; and mobilise domestic resources while strengthening local manufacturing of essential commodities. Most importantly, she said, mothers, adolescents and children must be partners, not merely beneficiaries, in designing the systems that serve them.

Dr. Mazyanga Lucy Mazaba, Regional Director for the Eastern Africa Regional Co-coordinating Centre of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, closed the session by stressing another existential threat to PHC: antimicrobial resistance (AMR). She warned that AMR undermines the gains of primary care by turning once-treatable infections into expensive, complex problems and straining already fragile health systems. Her priorities were clear: strengthen surveillance and diagnostics at the primary-care level, implement stewardship programmes, secure reliable supply chains for quality medicines, and invest in local capacity for manufacturing and quality assurance.