Financing Health in Africa: The Role of Health Taxes in Tackling NCDs

Vivianne Ihekweazu and Chioma Nnamani

As international aid continues to decline, Africa leaders are under pressure to find sustainable ways to financing healthcare. The increasing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), has made prevention and domestic resource mobilisation more urgent than ever, fuelling a changing sentiment towards health taxes. Governments are recognising that levies on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages can serve a dual purpose, reducing harmful consumption and providing a reliable source of domestic revenue.

How can African countries fund their own health systems in an era of shrinking Official Development Assistance (ODA)?

With aid to the continent slashed by nearly 70% in recent years, governments are under growing pressure to identify domestic financing solutions. One option gaining momentum is the introduction of health taxes, levies on products such as tobacco, alcohol, and other harmful commodities, not only to raise much-needed revenue but also to curb the rising tide of non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

A major setback came in January 2025, when the United States Agency for International Development USAID, paused significant funding. On paper, this cut represents less than 1% of the gross national income of most African countries. In practice however, the impact has been severe, undermining health programmes for HIV/AIDS, malaria, maternal health, pandemic preparedness, and more.

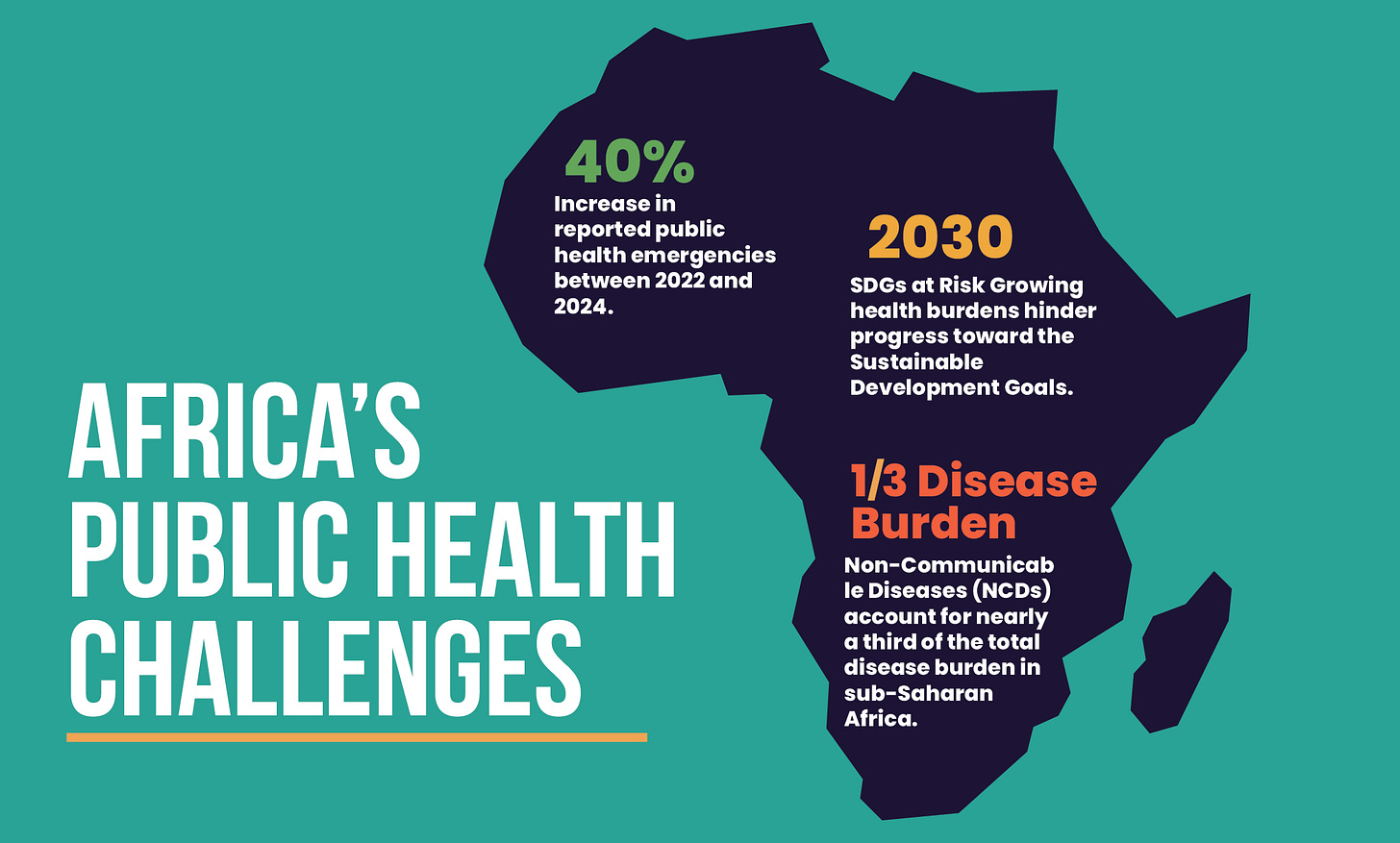

At the same time, Africa’s health systems are under intensifying strain. Between 2022 and 2024, the continent recorded a 40% increase in reported public health emergencies. Alongside these shocks, the growing burden of NCDs now accounts for nearly a third of the total disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa, hindering progress toward the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

This has resulted in African governments exploring new financing models to protect and strengthen health systems. Health taxes are increasingly at the centre of this conversation, offering a dual benefit, raising domestic revenue while reducing the risk factors that are driving NCDs.

Funding health through targeted taxes

Described by WHO as ‘Best Buys’, health taxes are intended both to curb consumption by making these products less affordable and to generate revenue that can be directed into health systems. Conversations about health taxes have become more pressing as governments look for sustainable ways to finance healthcare while reducing the impact of noncommunicable diseases. The WHO’s new report, Saving lives, spending less: the case for investing in noncommunicable diseases, presents the investment case, showing that adopting cost-effective interventions, such as health taxes would require countries to spend only about $3 per person each year, yet every $1 invested could yield around $7 in economic and social returns.

These measures are also central to the upcoming 4th High Level Meeting of the UN General Assembly (UNGA), where the Political Declaration on NCDs and Mental Health will be adopted. The declaration sets ambitious goals to reduce the toll of NCDs. However, the final draft has been met with criticism. The zero draft proposed higher taxes on alcohol, tobacco, and sugar-sweetened beverages, but the reference to sugar-sweetened beverages was removed in the final text. This dilution has drawn criticism given the strong evidence on the harms of sugary drinks, and it demonstrates the extent to which the commercial determinants of health, shaped by harmful commercial practices and industry influence can undermine evidence-based policymaking.

Speaking at the recent Africa Health Sovereignty Summit that took place in Accra on the issue of health taxes, former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown, pointed to the potential of health taxes as a powerful tool for both public health and domestic resource mobilisation. He pointed out that in the United Kingdom, tobacco is taxed at 80%, in addition to levies on alcohol and sugary beverages.

Building on this, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of WHO highlighted at the same summit that “a 50 percent price increase on harmful products like tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks could generate an additional USD 3.7 trillion globally within five years and save millions of lives.” Evidence from the report The Future of Health Financing in Africa: The Role of Health Taxes, further reinforces this point, showing that such taxes can not only plug the gap left created by shrinking donor support but also provide a critical pathway for addressing Africa’s escalating NCD burden.

During a recent webinar on the report’s findings, Dr. Mary-Ann Etiebet, CEO and President, Vital Strategies noted that;

“Over 90% of countries across the continent already have some kind of health tax in place, but the opportunity in front of us is to make sure countries are able to maximize and optimise the triple win that health taxes can create for their citizens and for their country.”

Several African countries are already putting health taxes to practice. In Botswana, a tax of BWP 0.02 per gram of sugar, which is over 4grams per 100ml was introduced in 2021 on sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs), this was after a 2014 levy that imposed 30 percent duty on tobacco production and imports. Ghana followed suit in 2023, shifting from an ad valorem tobacco tax to a hybrid structure that combines a 50 percent tax on factory prices with a specific levy of 5.60 cedis per cigarette pack. This lifted tobacco tax share from 23% in 2020 to 38% in 2024, doubling revenue to more than GHS 187 million.

Nigeria under the Finance Act of 2021, introduced an excise duty of ₦10 per litre on non-alcoholic, carbonated, and sweetened beverages which took effect in June 2022. This is expected to reduce the rise of NCDs such as diabetes and obesity while generating revenue. In Zimbabwe, the government announced a 0.5% fast food tax implemented from 1 January 2025, targeting sales at fast food outlets to reduce the consumption of highly processed foods. Within six months, the levy had generated nearly US$1 million.

South Africa’s 2018 Health Promotion Levy on sugary drinks remains one of the most notable examples. After implementation, a study of over 3,000 households found that the Health Promotion Levy led to a 51% drop in sugar intake, a 52% reduction in calories, and a 29% decrease in daily purchases of taxed beverages per person. The Health Promotion Levy generated R5.8 billion in its first two years, representing 0.2% of government revenue. However, the funds were not earmarked for specific health programmes and were allocated to the country’s general revenue.

Beyond these, other African countries have also introduced significant measures. Gabon levies a 5% excise tax on sugary drinks, alongside alcohol taxes ranging from 22% to 40% on beer, wine, and spirits. Cabo Verde raised its tobacco excise taxes above ECOWAS minimums, implementing changes in 2019 and 2021 that raised a special consumption tax from 30% to 50%, while Mauritius advanced its health taxation with tax share on cigarettes reaching nearly 78% by 2024, and an excise duty of 12 cents per gram of sugar on beverages, as part of efforts to curb the country’s high rates of obesity and diabetes.

Although health taxes have proven effective at reducing harmful consumption and raising revenue, many African countries have not designed policies and frameworks that earmark these funds for health-specific programmes. In many cases, poor design leaves the taxes vulnerable to inflation and industry interference which limits their impact on public health. It is important to ensure that these taxes are protected, transparently managed and used to improve population health outcomes.

Why this matters

Health taxes are more than just a tool to raise government revenue, they are an avenue to protect people from preventable diseases. By raising the purchasing price of tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks, there is a decrease in consumption, reducing the burden of non-communicable diseases. When health tax revenue is reinvested wisely, they can be used to strengthen health systems, fund prevention programmes, and improve access to treatment for vulnerable populations.

Without clear allocation of these funds, the full potential of health taxes is lost, and governments miss the opportunity to simultaneously improve public health and financial sustainability. All eyes will now be on the 4th High-level meeting of the UN General Assembly where the Political Declaration on NCDs and Mental Health will be adopted, raising the prospect of health taxes being prioritised as part of national strategies, providing countries with a renewed opportunity to reinforce their commitments to addressing NCDs.