Ethiopia’s Primary Health Care Reform - Lessons Africa Can Learn and Act On

Oladimeji Solomon Yemi

Over the past two decades, Ethiopia has built one of Africa’s most enduring public health success stories; a transformation rooted in community empowerment, domestic financing, and political continuity. From the Health Extension Programme to the PHC Re-envisioning Initiative, its journey shows how leadership, data, and accountability can redefine national health systems. Today, this model is a blueprint for African-led reform, adapted by countries like Nigeria, Ghana, Rwanda, Kenya, and Zambia.

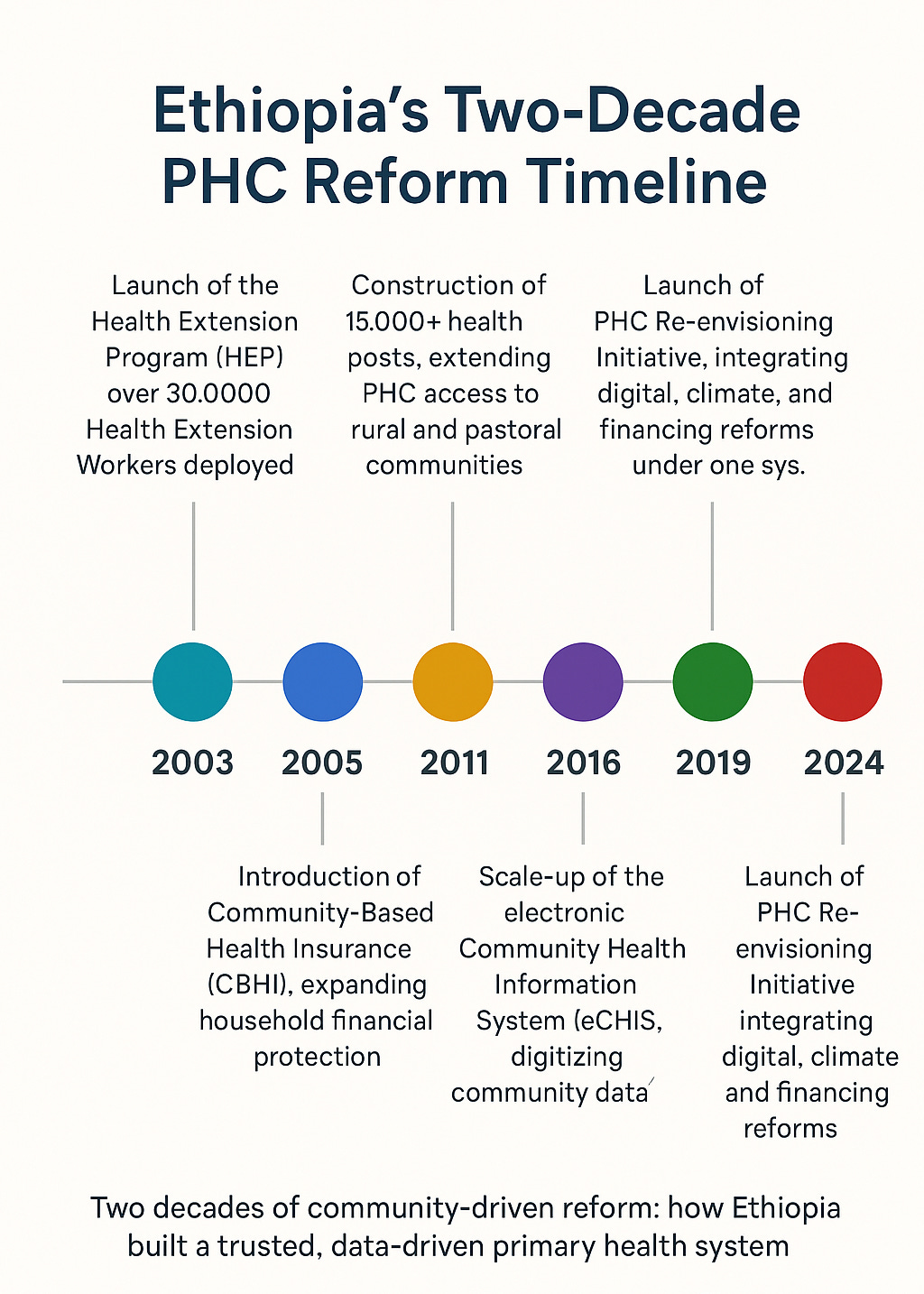

A Two-Decade Journey of Reform and Results

Ethiopia’s health reform began with a radical premise: health equity must start at the household level.

The centrepiece was the Health Extension Programme which trained over 30,000 Health Extension Workers (HEWs); mostly women to deliver essential care and health education in rural communities. Within five years, this effort led to the construction of over 15,000 health posts, dramatically improving access to preventive and basic curative services.

Subsequent phases of reform focused on strengthening integration, quality, and financing:

Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI) protected households from catastrophic health spending and built trust in the public system.

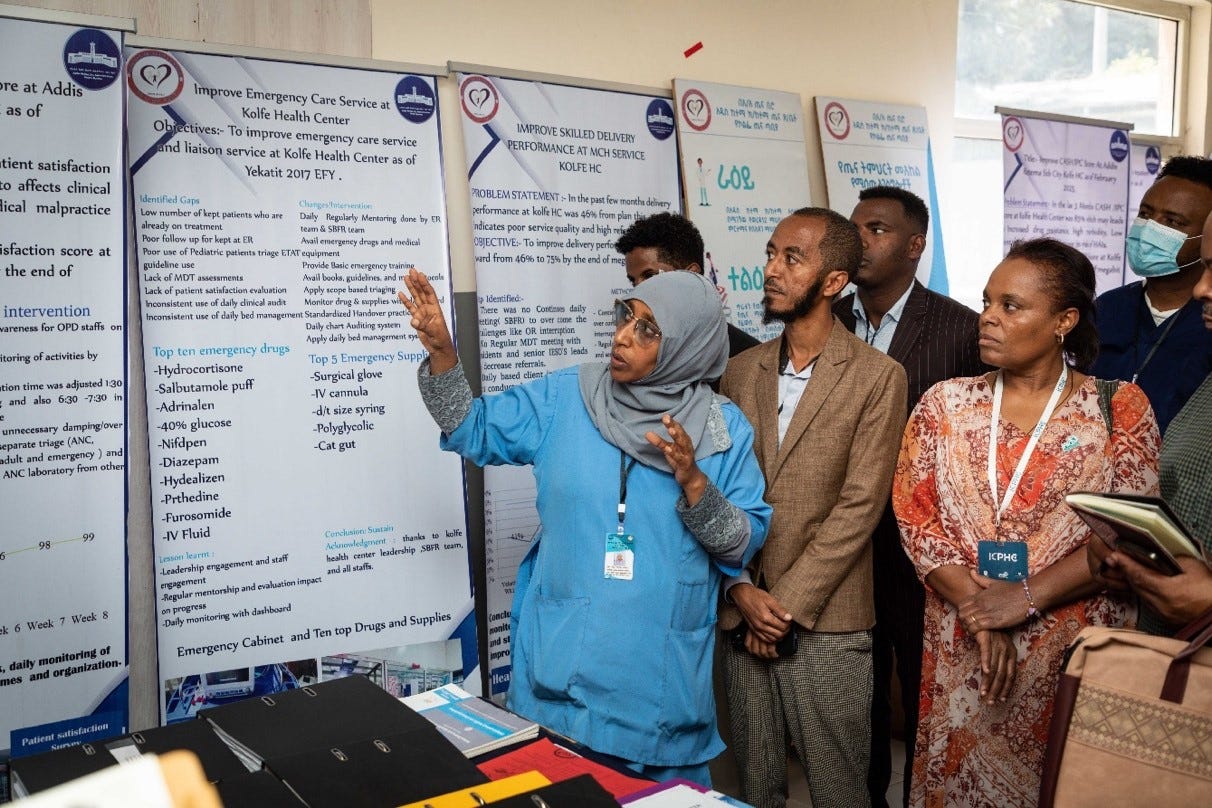

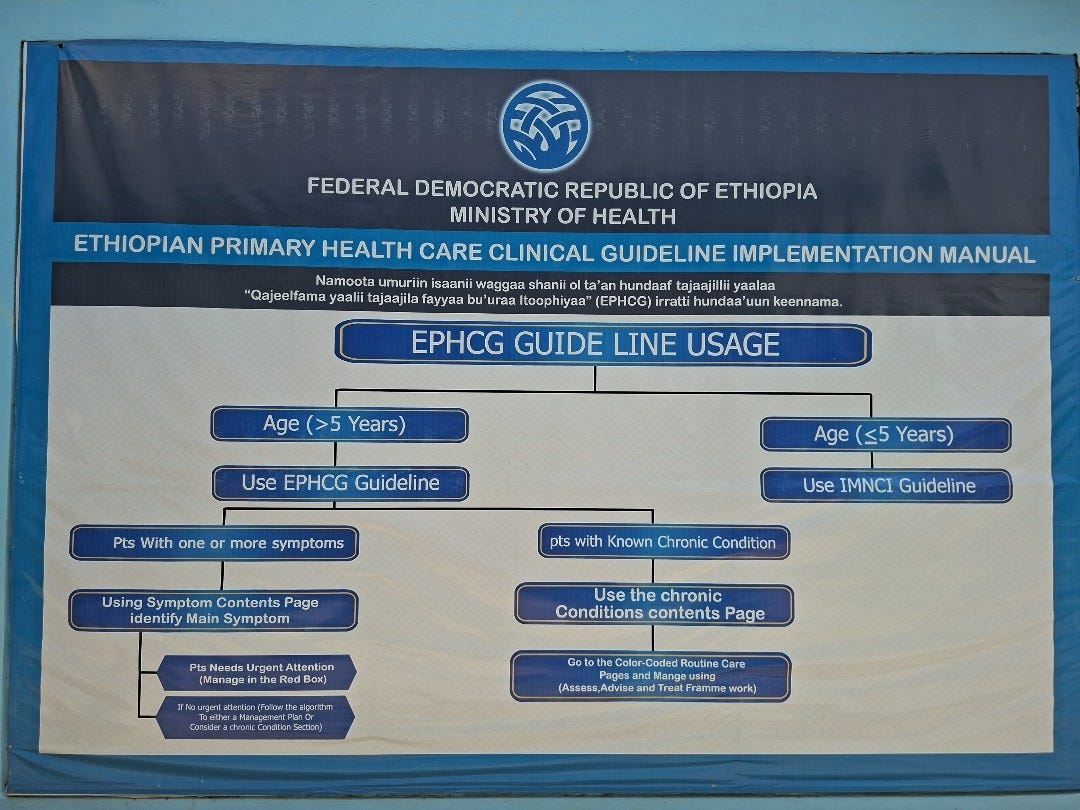

Ethiopian Primary Health Care Clinical Guideline (EPHCG) standardised care through clear, symptom-based protocols. Displayed visibly in facilities.

Electronic Community Health Information System (eCHIS) digitised the work of HEWs, linking local data to national dashboards and performance tracking.

Ethiopia’s health system is deeply data-driven. Health information is not stored in reports, it shapes decisions every day, guiding how services are delivered and how performance is measured across all levels of care.

By the time the Ministry of Health introduced the PHC Re-envisioning Initiative, Ethiopia had already demonstrated measurable progress in maternal mortality, immunisation, and service utilisation. These early gains positioned PHC as the essential foundation for the country’s universal health coverage agenda.

Recent data highlight the impact of Ethiopia’s two-decade health reforms. Maternal mortality fell by 72% since 2000, while neonatal mortality declined by 44%, outcomes directly reflecting two decades of sustained investment in community-based primary care and maternal health services. Ethiopia’s Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI) now reaches many districts, providing financial protection for households and deepening public trust in health facilities, according to recent Ministry of Health factsheets.

At the same time, Ethiopia’s renewed investment in local pharmaceutical production has increased domestic supply to 36% of national medical needs, saving the country more than US$53 million annually through import substitution and expanded manufacturing capacity. Together, these gains demonstrate how political continuity, community-based financing, and integrated health system integration are driving measurable progress toward universal health coverage in Ethiopia.

From Biyo to Bika: Where Policy Meets People

In Oromia’s East Shoa Zone, two facilities; Biyo Comprehensive Health Centre and its satellite, Bika Health Post, demonstrate how national reform translates into daily life.

At Biyo, facility dashboards track immunisation coverage, health insurance enrolment, and service quality. At Bika, HEWs provide antenatal care, child immunisations, and even trachoma trichiasis surgery, referring complex cases back to Biyo. The two facilities operate as a single ecosystem, reflecting Ethiopia’s philosophy of continuum-based care, one that connects data, financing, and accountability at every level.

Each case treated at the community level represents more than a health outcome; it reflects financial protection and trust in the system. By bringing essential services closer to families, Ethiopia’s PHC model reduces out-of-pocket costs and reinforces confidence in public facilities. This proximity-based trust has become a defining feature of the country’s health reforms, proving that accessibility and credibility grow hand in hand. Evidence from Ethiopia shows that community-based health insurance (CBHI) membership is associated with increased health service utilisation and reduced financial risk, while citizens’ trust in the scheme is shaped by perceived service quality and prior experience.

The Power of Political Ownership

What distinguishes Ethiopia’s PHC model is not only its structure, but its durability. Health has remained a consistent political priority across successive governments, supported by strong domestic financing and institutionalised accountability mechanisms. Over the years, vertical donor programmes have been systematically integrated into the national PHC framework, while domestic budgets have ensured sustained investment and high execution rates in the health sector. Recent analyses reveal that Ethiopia’s PHC reforms rest on three pillars, governance structures, data systems, and financial mechanisms that build resilience. This durability does not stem from the absence of challenges, but rather from sustained political commitment that persists regardless of changes in leadership or donor priorities.

Across Africa: Parallel Pathways of Reform

Across Africa, governments are redefining how primary health care is financed, delivered and governed, and Ethiopia’s model captures this shift, reflecting a broader continental momentum for homegrown reform.

In Nigeria, PHC funding has been embedded into law through the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), allocating 1% of consolidated revenue for frontline care. Under the Health Sector Renewal Investment Initiative (NHSRII), more than 17,000 PHCs are being revitalized, with state-level insurance schemes expanding coverage for vulnerable groups.

Ghana has followed suit, unlocking GHS 3.5 billion to provide free PHC services through the Accra Reset, reframing health as a domestic investment rather than an external obligation. Rwanda, meanwhile, continues professionalising its community health workforce, strengthening referral links between village-level care and district hospitals, and expanding digital PHC platforms to improve service delivery.

Kenya’s devolution embeds community health units in county systems, using digital health to connect telemedicine with maternal and newborn care. Zambia has integrated community health assistants into the civil service payroll, advancing the Lusaka Agenda. Together, these shifts reflect a move from donor dependence to fiscal sovereignty, parallel programmes to integration, and rhetoric to measurable delivery.

Shared Enablers of Success

Across these contexts, several enablers consistently emerge:

Political Commitment Anchored in Law: When PHC financing is codified in legislation, as in Ethiopia and Nigeria, it outlasts electoral cycles.

Domestic Resource Mobilisation: Ghana’s health levy and Ethiopia’s local insurance pools show how national treasuries can drive coverage.

Data Visibility and Use: Dashboards in Ethiopia, scorecards in Rwanda, and digital registries in Kenya make accountability visible and actionable.

Empowered Frontline Workforce: The professionalisation of HEWs and CHWs in Ethiopia, Zambia, and Rwanda remains the backbone of sustainability.

Community Trust and Participation: CBHI models, citizen scorecards, and ward committees ensure reforms are not imposed but co-owned.

Sustainability in primary health care is not achieved through funding alone. It is built on ownership; by governments, communities, and frontline workers and reinforced through trust. Where citizens feel heard and invested, health reforms endure long after external support fades.

A New Chapter in African Health Reform

Ethiopia’s PHC re-envisioning phase now integrates digital data, climate resilience, and financing into a future-ready system. Its deeper contribution is proof that systemic change is possible within a generation when reforms are politically anchored, financially domestic, and socially owned.

Across Africa, governments are redefining health sovereignty through accountable partnerships. The next phase is not about new models but scaling what works, investing in communities, data, and governance to build resilient, trusted health systems.

According to Dr. Jean Kaseya, Director-General, Africa Centre for Disease Control;

“The future of Africa’s health will be built at the primary level or not at all.”

Why This Matters

Ethiopia’s PHC journey shows that reform is not a one-time act but a generational commitment. By investing in trust, data, and domestic ownership, Ethiopia, like many of its peers; is rewriting the story of African health systems from dependency to dignity.

It is a reminder that the path to universal health coverage will not be paved by external aid alone, but by citizens, communities, and countries choosing to own their systems, and to believe in their power to sustain them.